The Financial Impact of Poor Process Design Inside Modern Organizations

Table of Contents

Introduction

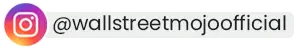

Poor process design is rarely discussed in financial terms, yet it shapes nearly every economic outcome inside an organization. Behind rising costs, delayed decisions, missed revenue, and execution failures, there is often a process problem rather than a strategic one. It is not a lack of talent or ambition. It is the presence of systems that no longer support how the business actually operates at scale. Over time, workarounds replace clarity, approvals multiply, and accountability becomes diffused.

In practice, poor process design shows up as rising labor costs, slower revenue realization, and declining margins long before it is labeled a “process problem.”

In modern organizations, processes determine how quickly decisions turn into action, how efficiently resources are allocated, and how reliably cash moves through the business. When those processes are poorly designed, financial performance erodes quietly and continuously. Teams spend more time coordinating than executing. Errors increase. Cycle times stretch. Customer expectations are missed. None of this shows up immediately as a single budget overrun or failed initiative.

Instead, the damage accumulates across departments, quarters, and strategic priorities. Margins thin. Forecasts become unreliable. Leadership responds by adding controls rather than removing friction. Without deliberate process design, financial leakage becomes embedded in daily operations, making underperformance feel normal rather than correctable.

What Poor Process Design Actually Is (And Why It’s Expensive)

Poor process design is not simply inefficiency or outdated workflows. It refers to systems that are misaligned with business goals, overly complex, poorly integrated, or dependent on unnecessary manual intervention. These processes typically evolve incrementally rather than being intentionally designed.

Adrian Iorga, Founder and President of Stairhopper Movers, explains, “Most process failures are not the result of bad decisions, but of accumulated decisions that were never revisited. What once made sense locally often becomes globally inefficient as the organization scales.”

As companies grow, they add approvals, tools, exceptions, and handoffs. Each change may solve a local problem, but together they introduce friction. What once worked at a smaller scale becomes slow, fragile, and expensive under pressure.

Poor process design typically shows up as:

- Excessive approvals with unclear decision ownership

- Redundant data entry across disconnected systems

- Manual workarounds that replace broken automation

- Processes that rely on institutional memory rather than documentation

These processes still function, but they do so at a higher financial cost than leadership often recognizes.

How Poor Process Design Causes Operating Costs to Scale Faster Than Revenue

One of the most immediate financial consequences of poor process design is higher operating costs. When workflows require unnecessary coordination, employees spend more time managing work than producing value. The organization becomes busy without becoming more productive, and costs rise long before revenue follows.

David Lee, Managing Director at Functional Skills, notes, “Rising operating costs are often treated as a staffing problem, when they’re actually a process design failure. Labor expands to absorb inefficiency long before revenue catches up.” This dynamic is common in growing organizations where processes have not evolved alongside scale. Instead of removing friction, teams compensate manually, embedding inefficiency directly into the cost structure.

#1 - Why Headcount Becomes the Default Solution

Manual handoffs, unclear decision rights, and disconnected systems force teams to rely on workarounds to keep work moving. These workarounds consume time, increase error rates, and reduce overall throughput. As pressure builds, leadership often responds by adding staff to stabilize delivery rather than redesigning the underlying process.

While this approach can relieve short-term strain, it permanently increases operating costs without improving efficiency. Output grows marginally, if at all, while labor expenses compound quarter after quarter. Over time, the organization becomes structurally expensive to run.

#2 - How Cost Pressure Quietly Accumulates

These cost increases rarely appear as a single line item. Instead, they surface gradually across multiple operational signals, including:

- Rising headcount without proportional output growth

- Increased overtime driven by coordination delays

- Higher administrative and managerial overhead

- Growing costs associated with error correction and rework

Because each increase seems incremental, the financial impact is often underestimated until margins begin to erode.

Where Financial Symptoms Actually Begin in the Workflow

What the table highlights is that financial impact rarely starts where it is ultimately measured. Costs surface in labor, margins, and cash flow, but their origin is almost always earlier in the workflow. By the time leadership sees a variance on a financial report, the underlying process failure has already propagated across teams, decisions, and timelines.

Brandy Hastings, SEO Strategist at SmartSites, explains, “Organizations often underestimate how many financial problems originate upstream. By the time costs appear in the P&L, the process failure has already occurred multiple steps earlier.” This lag between cause and visibility makes process-related financial risk difficult to diagnose using traditional reporting alone.

#1 - The Delay Between Cause and Financial Visibility

Most financial metrics are backward-looking by design. They summarize what has already happened rather than revealing how it happened. When a process breaks down, the initial impact appears as delays, rework, or confusion at the operational level. These issues only register financially after they have accumulated into overtime, missed deadlines, or lost opportunities.

As a result, leadership often reacts to financial symptoms without seeing the operational chain that created them. Cost overruns are treated as budget discipline issues. Margin pressure is attributed to pricing or market conditions. Cash flow volatility is blamed on timing or demand. In reality, each of these outcomes may trace back to the same poorly designed process upstream.

#2 - Why Financial Fixes Alone Rarely Work

This disconnect explains why purely financial fixes often fall short. Hiring freezes, budget cuts, or stricter approval thresholds may temporarily suppress costs, but they do not remove the friction that created those costs in the first place. In many cases, they intensify it by adding more constraints to already inefficient workflows.

When processes remain unchanged, inefficiencies simply reappear elsewhere. Delays move downstream. Errors shift between teams. Costs resurface under different categories. The organization expends energy controlling symptoms instead of eliminating their source, reinforcing financial leakage rather than resolving it.

#3 - Shifting the Lens Upstream

Sustainable financial improvement requires shifting attention upstream, to where work actually moves and decisions are made. When leaders understand how processes translate directly into financial outcomes, they can intervene earlier, before inefficiencies harden into recurring costs. This shift turns process design from an operational concern into a core financial discipline, directly tied to margin protection, forecast reliability, and long-term scalability.

Revenue Lost to Delay and Inertia

Poor process design limits revenue growth not by eliminating demand, but by slowing the organization’s ability to act on it. In competitive markets, speed is often the deciding factor between capturing opportunity and watching it move elsewhere. When internal processes create friction, revenue does not disappear dramatically. It leaks away through hesitation, rework, and missed timing.

#1 - How Slow Processes Stall Revenue

Delays compound at every stage of the revenue cycle. What seems like a minor internal slowdown often becomes a customer-facing failure.

- Approvals that take days instead of hours cause deals to cool or stall

- Pricing changes that require multiple sign-offs extend negotiations unnecessarily

- Unclear onboarding steps increase customer hesitation and early drop-off

- Sales teams spend time navigating the process instead of closing

Each of these delays reduces conversion probability, even when interest is strong.

#2 - Inertia as a Strategic Constraint

More damaging than individual delays is the broader effect of inertia. Slow internal processes limit an organization’s ability to respond to market shifts. Product launches slip. Competitive responses lag. Promotions miss their moment.

Even when demand exists, revenue remains unrealized because the organization cannot move fast enough internally. Over time, speed becomes a competitive disadvantage rather than a capability, turning operational friction into a structural revenue ceiling.

Cash Flow Disruption and Working Capital Drag

Poor process design frequently disrupts cash flow. Delayed invoicing, billing errors, inconsistent approvals, and slow collections all affect how quickly cash moves through the business.

Common process-related cash flow issues include:

- Delayed or inaccurate invoicing

- Slow approvals for billing and collections

- Poor alignment between fulfillment and finance systems

When fulfillment and billing are not tightly integrated, invoices are issued late or inaccurately. Days' sales outstanding increase, tying up working capital. Businesses may appear profitable while struggling to fund operations.

Procurement inefficiencies create similar strain. Poor purchasing processes lead to over-ordering, rushed buying, missed payment terms, and excess inventory. Cash becomes trapped in stock rather than available for growth or resilience.

These issues often increase reliance on external financing, raising interest costs and reducing financial flexibility.

Increased Risk and Compliance Exposure

From a financial perspective, risk represents potential cost, not abstract uncertainty. Poor process design increases this cost by reducing consistency, visibility, and control across day-to-day operations. When processes are unclear or inconsistently followed, organizations lose their ability to detect issues early, making small problems more likely to escalate into expensive failures.

- Compliance Breakdown and Regulatory Consequences: In regulated environments, inconsistent processes often lead directly to compliance gaps. Documentation is incomplete, approvals are missed, and audit trails become unreliable. These weaknesses increase the likelihood of regulatory findings, fines, remediation costs, and ongoing monitoring requirements. Even minor violations can consume significant financial and managerial resources once formal reviews are triggered.

- Operational Risk Beyond Regulation: In less regulated sectors, weak process design still creates substantial financial exposure. Informal workflows and unclear controls increase the risk of fraud, human error, and financial misstatement. When accountability is diffuse, incidents take longer to identify and correct, allowing losses to compound before action is taken.

- Process Strength as a Risk Control: Strong processes function as built-in risk controls. They create consistency, traceability, and clear ownership. Weak processes do the opposite. They amplify exposure, increase incident impact, and gradually erode trust with customers, partners, and investors, raising the long-term cost of doing business.

Technology Spend Without Return

Many organizations attempt to solve process problems by adding new technology. When underlying workflows are unclear or poorly designed, this approach rarely delivers meaningful financial returns. Instead of improving performance, technology often amplifies existing inefficiencies, locking them in at greater scale and cost.

Kos Chekanov, CEO of Artkai, explains, “Technology delivers returns only when it reinforces a clear process. When it replaces clarity, it creates the illusion of progress while compounding inefficiency.”

Automating a broken process does not correct its flaws. It accelerates them. Errors occur faster. Data moves more quickly but remains inconsistent or incomplete. Teams struggle to adapt because the system reflects outdated assumptions rather than how work actually happens. Over time, confidence in the tools erodes, and manual workarounds return.

This dynamic commonly leads to tool sprawl:

- Multiple systems performing overlapping functions

- Fragile integrations that require constant maintenance

- Rising license and implementation costs with limited usage

- Increased training time and onboarding friction

Employees end up spending more effort navigating tools than executing meaningful work. As a result, technology budgets expand while productivity plateaus. The problem is rarely the software itself. It is the process foundation that it was built upon. Without redesigning workflows first, technology investment becomes an expense rather than a multiplier.

Employee Turnover and Its Financial Impact

Process design plays a direct and often underestimated role in shaping employee experience. Workflows filled with friction, ambiguity, and unnecessary manual effort create daily frustration. When capable employees spend their time navigating broken systems instead of doing meaningful work, disengagement sets in. High performers, who have the most options elsewhere, are often the first to leave.

#1 - The Direct Cost of Attrition

Employee turnover carries immediate and measurable financial costs. Recruiting replacements requires time, advertising spend, and management involvement. Onboarding and training consume additional resources before new hires reach full productivity. During these transitions, teams operate below capacity, and output suffers.

#2 - Burnout as a Process Problem

Poorly designed processes accelerate burnout by forcing employees to compensate for system failures. They memorize steps that should be automated. They chase approvals that should be clearly defined. They resolve issues that could have been prevented through better design. Over time, this constant friction erodes morale and trust in leadership.

#3 - Compounding Financial Consequences

As attrition rises, institutional knowledge disappears, and error rates increase. Remaining employees absorb extra workload, intensifying fatigue and turnover risk. The organization pays not only in replacement costs, but in lost momentum, reduced quality, and long-term damage to culture and performance.

Strategic Drift and Misallocated Capital

When processes are misaligned with strategy, financial decisions deteriorate quietly but predictably. Leadership may set clear strategic priorities, yet without supporting processes, capital allocation drifts away from execution reality. Investments are approved based on intent rather than operational readiness, weakening return on capital and increasing financial risk.

Organizations often invest in growth initiatives while their core processes remain optimized for stability and control. Conversely, they may pursue aggressive cost reduction while maintaining workflows that encourage redundancy, rework, and manual intervention. In both cases, strategy and execution operate on different assumptions, creating structural inefficiency.

As processes fail to support strategic objectives, financial metrics lose reliability. Forecasts reflect aspiration rather than capacity. Performance indicators lag behind reality. Capital decisions are made using incomplete or distorted information, increasing the likelihood of misallocation.

Common signs of strategic drift driven by poor process design include:

- Capital is invested in initiatives that stall due to operational constraints

- Projects are exceeding budgets because processes cannot absorb complexity

- Technology spend increasing without corresponding productivity gains

- Growth initiatives are underperforming due to slow decision cycles

- Cost-reduction programs failing to deliver sustainable savings

Over time, capital is deployed inefficiently across projects that compete for attention, resources, and approvals. Execution slows, priorities blur, and initiatives lose momentum. Returns fall short not because the strategy was flawed, but because the underlying processes could not support it.

Poor process design turns capital into sunk cost rather than strategic leverage. Instead of amplifying competitive advantage, investment becomes fragmented and reactive. For organizations seeking consistent financial performance, aligning process design with strategic intent is essential to protecting capital efficiency, improving return on investment, and preventing long-term strategic drift.

How Poor Processes Distort Financial Visibility

Poor process design does more than increase operating costs. It undermines the quality and reliability of financial insight. When data moves through fragmented systems, manual handoffs, or inconsistent workflows, reporting becomes slow, incomplete, or contradictory. Finance teams are forced into constant reconciliation mode, spending time fixing numbers instead of analyzing them.

#1 - Delayed and Distorted Reporting

Manual inputs, duplicate data entry, and unclear ownership introduce delays and errors into financial reports. By the time figures are consolidated, they often reflect past conditions rather than current performance. This lag reduces the usefulness of financial data for day-to-day decision-making and risk management.

#2 - Forecasting Detached From Reality

When processes do not reflect how work actually gets done, forecasts rely on assumptions instead of operational signals. Budgets are built on averages and historical trends rather than live inputs. Variances appear without clear explanations, weakening confidence in planning models and financial guidance.

Andrew Bates, COO of Bates Electric, explains, “Many financial blind spots originate outside the finance function, where inconsistent workflows quietly disconnect forecasts from reality.”

#3 - Strategic Decisions Made in the Dark

The cost is not limited to poor reporting. Leadership decisions are made with limited visibility into real-time performance. Without accurate, timely data, executives respond later, adjust more slowly, and commit resources with greater uncertainty. Over time, distorted financial visibility becomes a structural handicap at the highest levels of the organization.

The Compounding Effect of Inaction

The most dangerous aspect of poor process design is how it compounds over time. Small inefficiencies accumulate. Workarounds become permanent. Delays push decisions further into the future.

What begins as minor friction becomes a structural constraint. Teams adapt around broken processes rather than fixing them. Financial performance declines gradually, often without a single identifiable cause.

Short-Term vs Long-Term Financial Effects of Poor Process Design

Poor process design rarely creates immediate financial crises. Instead, its impact unfolds gradually, becoming more expensive and harder to reverse over time. What initially appears as minor operational friction slowly compounds into structural financial constraints. The longer inefficiencies persist, the more deeply they embed themselves into the organization’s cost base, revenue mechanics, and decision-making behavior.

The table below shows how the consequences of poor process design evolve across different time horizons. At each stage, the signals become more visible to leadership, but the financial cost of correcting them increases.

| Time Horizon | What Leaders Notice | What Happens Financially |

|---|---|---|

| Short term | Minor delays and friction | Hidden cost increases |

| Medium term | Slower execution | Revenue leakage and cash strain |

| Long term | Structural bottlenecks | Margin compression |

| Very long term | “Too risky to change” mindset | Persistent financial drag |

In the early stages, inefficiencies are absorbed quietly through overtime, rework, or informal coordination. Because financial performance still appears stable, these costs remain largely invisible. As time progresses, delays begin to affect revenue timing, customer experience, and cash flow reliability. Eventually, bottlenecks harden into the operating model, limiting scalability and compressing margins.

By the time leadership intervenes, change feels risky and disruptive. Teams have adapted to inefficient processes, dependencies are tightly coupled, and the cost of delay has already been paid repeatedly. At this point, poor process design is no longer an operational inconvenience. It has become a persistent financial drag that undermines long-term performance.

Process Debt and Long-Term Cost Accumulation

Just as technical debt accumulates in software systems, process debt builds up quietly in day-to-day operations. Each workaround, exception, manual override, or “temporary” fix adds a layer of hidden complexity that must be remembered, explained, and maintained. These changes rarely feel significant in isolation, but together they reshape how work actually gets done.

At first, process debt appears manageable. Teams adapt. Informal knowledge fills the gaps. Over time, however, the cost becomes visible. Coordination slows as fewer people fully understand the workflow. Training new employees takes longer. Error rates rise as edge cases multiply. What once felt flexible becomes fragile.

William Fletcher, CEO of Car.co.uk, explains, “Process debt is dangerous because it hides in normal work. By the time leadership sees the cost, it has already been paid repeatedly through delay, rework, and lost flexibility.”

As process debt grows, the organization’s ability to change declines. New initiatives are harder to launch because existing workflows cannot absorb additional variation. Technology implementations take longer. Strategic shifts stall under operational strain.

Eventually, leaders face a reckoning. They either invest in deliberate process redesign or accept persistent financial drag. The longer the process debt is ignored, the more disruptive and expensive it becomes to unwind, turning past shortcuts into long-term constraints on growth and performance.

Why Process Design Delivers Outsized ROI

Unlike many strategic initiatives, process improvement does not require heavy capital investment or long implementation cycles to generate results. Its impact comes from removing friction rather than adding complexity. Small, well-targeted changes often unlock disproportionate financial returns because they address constraints that affect multiple parts of the organization simultaneously. When a bottleneck is removed, benefits cascade across teams, timelines, and cost structures.

High-impact process improvements typically focus on fundamentals rather than transformation programs:

- Clarifying ownership for key decisions to reduce delay and rework

- Removing unnecessary approval layers that slow execution without reducing risk

- Eliminating redundant steps across functions that add cost but no value

Improved processes lower operating costs while increasing effective capacity. Teams spend less time coordinating and more time executing. Cycle times shrink. Output becomes more predictable. Importantly, these gains are achieved without adding headcount, tools, or overhead.

For finance and operations leaders, this makes process design one of the most underutilized levers for performance improvement. It improves efficiency, resilience, and financial clarity at the same time, delivering returns that compound as the organization grows rather than diminishing with scale.

Conclusion

The financial impact of poor process design is real, measurable, and often underestimated. It appears in higher costs, lost revenue, strained cash flow, elevated risk, distorted visibility, and weakened strategic execution.

Organizations do not fall behind because they lack intelligence or ambition. They fall behind because their systems no longer support the way the business needs to operate.

Process design is not about perfection. It is about alignment. When processes align with strategy, financial performance follows. When they do not, even strong strategies struggle to deliver results.

In modern business, process design is not an operational concern. It is a financial imperative.

For organizations seeking durable financial performance, process design is no longer optional. It is a prerequisite for sustainable growth.