Table of Contents

What Is A Securitized Debt Instrument (SDI)?

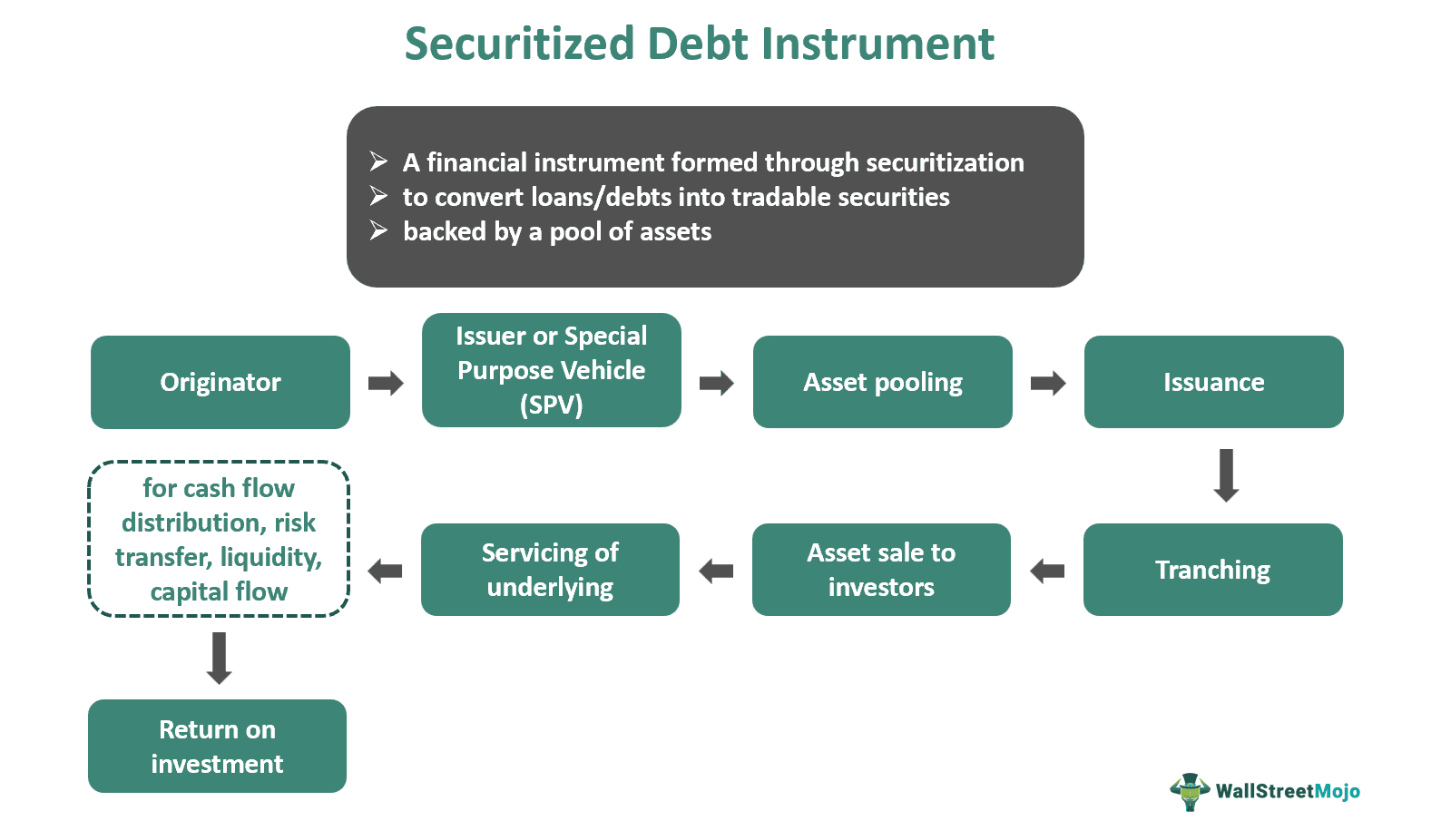

A Securitized Debt Instrument (SDI) refers to a financial instrument created through the securitization of loans or debts. Securitization is a financial procedure wherein securities backed by a pool of assets, usually debt (loans, mortgages, etc.), are issued. This process transforms assets into securities, thus termed securitization.

SDIs stand out for their potential for superior returns compared to other fixed-income options like corporate bonds. It offers investors the opportunity to earn fixed, predictable returns. This advantage is grounded in two fundamental elements of SDI design: clearly defined returns linked to a specific underlying asset and a strong security structure.

Key Takeaways

- Securitized Debt Instruments (SDIs) are financial assets derived from securitizing individual loans or debts, offering potentially superior returns compared to other fixed-income options.

- The securitization process involves two stages: asset aggregation and sale to an issuer, usually a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). The issuer then issues interest-bearing securities to investors, who receive payments from a trustee funded by cash flows.

- SDIs include mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities, collateralized debt, credit default swaps, and securitized financial products facilitated by SPVs.

- The advantages of SDIs include reduced borrowing costs, flexible risk profiles, and risk transfer, while quality diminishment, high expenses, complexity, and interest rate vulnerability are some disadvantages.

How Does A Securitized Debt Instrument Work?

Securitized Debt Instruments are financial securities established through the process of securitization, wherein loans or receivables are converted into securities. This process results in the generation of financial assets. These securities are backed by different assets, like debt instruments, mortgages, credit card debt, auto loans, etc., and serve as financial instruments within the securitization framework.

In its essence, securitization comprises two primary stages. Initially, a company, known as the originator, identifies income-producing assets, aggregates them into a reference portfolio, and sells them to an issuer to eliminate them from its balance sheet. They are commonly known as Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs). Secondly, the issuer secures the acquisition of these assets by initializing the issue of interest-bearing securities to interested investors in the secondary market. Investors then receive payments from a trustee, which is funded by cash flows generated by the reference portfolio.

Typically, the originator manages the loans in the portfolio, gathers payments from the original borrowers, channels them after deducting a servicing fee, and sends it directly to the SPV or trustee. This process presents a varied financial source. It helps in shifting credit risk, along with potential interest rate and currency risk, from issuers to investors.

Securitization offers lenders liquidity and helps diversify portfolios to mitigate risks. Debt instruments are pooled and sold in smaller segments called tranches, where each tranche represents a share of receipts from the underlying instruments of debt. Tranching allows smaller investors to participate and enables lenders to access more capital by selling to a wider market.

Types

Since SDIs are a means of generating worthwhile financial assets that hold the potential to give handsome returns, it is important to understand their types. We will discuss them below.

- Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): MBS are transactions backed by mortgage loans, either Residential MBS (RMBS) or Commercial MBS (CMBS).

- Asset-Backed Securities (ABS): These are securities supported by stable cash-flow generating assets like mortgages, corporate loans, and consumer credit, which are structured into reference portfolios.

- Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO): These are structured like ABS but encompass a wider array of assets. It includes variations such as Collateralized Bond Obligation (CBO), Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO), and Collateralized Mortgage Obligations (CMO).

- Credit Default Swaps (CDS): These financial derivatives offer investors the option to swap or offset credit risk with fellow investors, serving as insurance against defaults.

- Securitized Financial Products (SFP): Under SFP, pools of assets form a security that is split and then sold to investors.

- Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV): SPVs are a subsidiary or separate entity from the offering company, isolating financial risk. It offers investor protection if the parent company faces financial issues like bankruptcy. It is also called a Special Purpose Entity (SPE).

Examples

In this section, let us study some examples to understand the concept better and see how these instruments are used by investors and businesses.

Example #1

Suppose Dannielle, an investor, decides to invest in asset-backed securities (ABS) for diversification and potential returns. She chooses an ABS backed by a pool of auto loans. The ABS is created by a financial institution that transfers the loans to a separate entity called a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV).

The SPV issues different tranches of ABS securities based on credit risk. Dannielle invests in the senior tranche for lower risk. As borrowers make loan payments, cash flows are collected by the SPV and distributed to ABS investors. The performance of Dannielle's investment depends on borrower payments and credit risk.

Stella, Dannielle's financial advisor, tells her that while ABS can provide diversification and potential returns, investors should be careful and understand the risks involved in investments before investing. Dannielle follows this piece of advice from Stella and invests further in various SDIs after careful deliberation, displaying prudent investor behavior. Stella’s advice also highlights the importance of effective risk management and regulatory supervision in the context of SDIs.

Example #2

The Securitization Committee recently released data on US mortgage-backed securities (MBS) statistics, focusing on the fixed-income market structure through a research report published in May 2024.

SIFMA Research diligently tracks the current landscape of MBS, providing insights into issuance, trading activities, and outstanding data. The data is meticulously categorized into agency and non-agency securities, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the MBS sector.

Notably, the latest figures reveal that YTD issuance, as of March, stands at $310.4 billion, marking a notable increase of 13.4% year-over-year. This data is available for analysis on a daily (for trading volumes only), monthly, quarterly, and even annual basis, enabling trend analysis and informed decision-making within the securitization domain.

Example # 3

A June 2023 Business Wire article discusses a securitization transaction. Tricon Residential Inc. planned to issue and sell fixed-rate certificates backed by a portfolio of single-family rental properties within the SFR JV-2 investment vehicle under the 2023-SFR1 securitization transaction. These certificates were offered through multiple financial institutions.

The assets received a credit rating from Moody’s Investors Service and Kroll Bond Rating Agency. This securitization deal was made to enable Tricon to raise funds by selling interest-bearing instruments on future cash flows from these rental properties. This illustrates how loans/debts/mortgages can be mobilized and used to raise funds.

Pros & Cons

Now that we have understood how SDIs work, let us study their pros and cons.

Pros

- SDIs reduce borrowing costs and regulatory capital requirements for corporations and banks.

- They enable companies to raise funds by selling asset pools to issuers, who convert them into tradable securities, separating them from the originator's balance sheet.

- Inflating a company's liabilities can be avoided; they help generate funds for future investment without adding strain to the balance sheet.

- SDIs offer flexibility in tailoring risk-return profiles of loans into tranches, aligning with investor risk preferences.

- Effective in both mature and emerging markets, SDIs facilitate the conversion of future cash flows into liquid capital.

- They facilitate risk transfer, taking risks away from entities unwilling to bear them and transferring them to the relevant parties, enhancing overall risk management strategies.

Cons

- It may diminish the quality of the investor's asset portfolio by leaving behind a riskier portfolio after securitizing certain tranches.

- They bring significant expenses to entities due to management and operational costs, including fees such as legal, administrative, underwriting, and rating.

- SDIs often require extensive structuring, making them less cost-effective for small and mid-size transactions.

- They come with inherently risky structures, like prepayment penalties and credit loss, inherent to structured transactions.

- SDIs are impacted by changes in interest rates, potentially impacting assets within the pool differently and affecting the overall securitization.

- Complexity, lack of transparency, credit risk, market risk, and potential systemic risks are other challenges entities face while dealing with SDIs.